Suchen und Finden

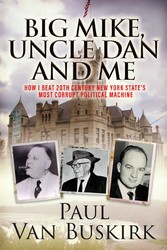

BIG MIKE, UNCLE DAN and ME - How I Beat 20th Century New York State's Most Corrupt Political Machine

Mehr zum Inhalt

BIG MIKE, UNCLE DAN and ME - How I Beat 20th Century New York State's Most Corrupt Political Machine

CHAPTER ONE

SITE OF THE FALLING CANOE

The area between the Adirondacks and the Catskill Mountains in upstate New York, the City of Cohoes is divided roughly into thirds: the Western plain plateau, the river plain, and Van Schaick Island, the fat finger of land near where the Mohawk River empties itself into the Hudson River from 170 feet above. The Cohoes Falls are generally accepted as the source of the city’s unusual sounding name. According to one story, “Cohoes” was a Dutch attempt at “ga-ha-oose,” the Mohawk word for “falling canoe.”

Even though Niagara Falls is only slightly larger than Cohoes Falls, the latter’s potential to draw tourists interested in nature’s more dramatic side seems to have escaped the notice of the public. The estimated number of tourists to visit Niagara Falls annually is about twenty-eight million people. In Cohoes, it’s nil.

However, the falls in Cohoes—among the largest east of the Rocky Mountains—has been the site of some dramatic feats of engineering. The first of these occurred during the American Revolutionary War when a Polish patriot designed and oversaw the construction of breastworks on Peebles Island, just north of Van Schaick Island, a worthy defense against the British crossing the only ford on the two rivers for many miles, as these bulwarks played an important part in the strategy for the Battle of Saratoga, the turning point of the war. Two hundred and thirty years later, these earthen structures remain largely intact.

Superb engineering also featured in the construction of the single lock system of the Erie Canal along the long, narrow Hudson–Mohawk River plain in 1817. This nearly 400-mile-long system of locks trapped water at one level and then released it again at a lower or higher level so that barges atop the water could make their way around geographical challenges. Ultimately, barges traveling along the canal ascended and descended 675 feet of water.

Of eighty-three locks, nineteen were constructed specifically to circumnavigate the Cohoes Falls, making it possible to connect Buffalo and the Great Lakes with New York Harbor. In 1836, when the canal was enlarged with double locks, the route remained mostly the same, with eleven locks in Cohoes. To this day, several of the Cohoes locks are in good condition, monuments to this historical engineering wonder. With the completion of the Champlain Canal that ran from Cohoes north to the St. Lawrence River, by 1823 the city had become a major transportation hub for supplies and people.

Its situation along the rivers also meant that beginning in 1831, when the Erie shipping canals were at the height of operation, Cohoes was a key player in the industrial revolution. By 1870, the city’s Harmony Mills were the largest water-powered cotton mills in the world, earning Cohoes the name “Spindle City.” Then a series of water-power canals were constructed above and below the falls, driving vertical turbine power in the mills built between the canals. The city’s population surged as mill workers arrived from French Canada, Ireland, Italy, and Eastern Europe, and were housed in hundreds of red brick row houses.

“Big Mike” Smith was among those whose parents emigrated from Ireland and found work in the mills in the 1860s. Big Mike was born on July 8, 1862, in Waterford, New York—not Ireland, as he liked to imply—just across the Mohawk River from Cohoes. When he was eight, his parents moved with him, his three brothers, and two sisters across the river to the Cohoes First Ward, into a Harmony Mills housing unit near an elementary school.

Mill workers and their families lived in well-constructed tenement homes, or in boarding houses if they were unmarried women. There were company stores for basic goods, a clinic, a volunteer fire company, and even a day care center. The mill’s operator, Garner & Company, also maintained the streets, and, as the largest landlord in Cohoes, had a corps of maintenance staff, including plumbers, masons, and mechanics. For those who’d known poverty, uncertainty, and abysmal working conditions back in “the old country,” it was an easy equation: stable pay, food, and shelter in exchange for loyalty and labor.

At the turn of the twentieth century, however, the mills were in distress, faltering under the pressure and competition of cheaper labor, power, and materials further south. Around that time, Big Mike, who’d once been a millworker and a lock tender, began running a saloon, right in the center of Harmony Mills housing and the Cohoes section of the Erie Canal. The saloon hosted clam steams, sponsored athletic teams, and became the hub for neighborhood news.

When the mills went belly-up, a power vacuum emerged that Big Mike would soon fill. He became the man to know if you needed a favor or wanted a job, a loan, a bucket of coal, or even a home. In return, you gave him your loyalty and your vote. People who were hit hard by the Depression figured this was a fair trade. Families in Cohoes that had once relied on the mills increasingly looked to a strongman like Big Mike for help and cover. In a sense, he became the new boss in town.

He was not the first political boss in our little city. You could say that European-style political patronage systems in America began in Cohoes. Around 1630, Dutch diamond and pearl merchant Kiliaen van Rensselaer paced off as his own an area at the confluence of the Mohawk and Hudson. The parcel was part of the original patroon that today is essentially the entire Albany Capitol District. Rensselaer’s bit of land marked by the rivers was approximately three miles wide and three miles long, and today marks the city of Cohoes. The Dutchman eventually sold off tracts to newcomers, keeping the area below the falls for himself.

The Dutch patroons in the Hudson River Valley had chartered rights to create civil and criminal courts, appoint local officials, and hold land in perpetuity. In return for these inducements, the patroon had to grow the manor’s population in increments of fifty every four years. Colonists were exempt from taxes for the first ten years they lived on the manor but were obligated to pay rent to the patroon, who often oversaw the creation of the manor’s infrastructure. Another way to say it is that the word of the patroon—what we’d call in English the patron—was law. Despite the passage of 200 years and a war fought against the British to end authoritarian rule, Cohoes steadfastly remained true to its patronage roots.

The textile manufacturing industry never recovered in Cohoes, and by 1960, the unemployment rate among men in Cohoes was still roughly 8.5%. The median family income was $5,573, although more than 15% of families lived on only about $3,000 a year. In today’s economy, that would be about $25,000. Also at that time, a third of Cohoesiers twenty-five years and older had less than eight years of education; for the other two-thirds of adults, just less than nine years was the average. According to the same year’s census, about a fifth of the couples in town were separated, widowed, or divorced, circumstances which often equated to either an onset or a deepening of poverty. Lastly, at least a third of the Cohoes citizenry was of foreign stock from French Canada, Ireland, Italy, Poland, Russia, and Ukraine.

This meant that more than a third of the Cohoes population in 1960 was relatively poor, foreign-born, uneducated, and raised according to the strict, authoritarian doctrine of a pre-Vatican II Catholic Church. That’s another way to say that for at least a third of Cohoesiers, fighting for individual rights using democratic processes was neither reflexive nor, given the demands of surviving day-to-day, a priority.

The effect on the town was that in place of the mills, Big Mike’s patronage system was a way to survive. His variation on a theme of Robin Hood—one for you, ten for me, but always with a wink and smile—bridged ethnic differences among the poor in town without alienating the powerful Catholic Church, with which he made sure to stress the common value of charity. To be Catholic in Cohoes also meant you were a Democrat, one of Big Mike’s own.

The Big Mike brand was so entrenched that more than a decade after his death, challenging his Democratic Party inheritors to stop pocketing the profits of patronage and do something about the crumbling infrastructure, rates of unemployment, slum living conditions, and overall despair would have been unthinkable to a population where religion, ethnicity, and political affiliation had grown inseparable. It was thought better to suffer the devil you knew rather than risk being exiled for asking for more.

U.S. Speaker of the House Thomas “Tip” O’Neill once said, “All politics is local.” In Cohoes, all local politics is centered in the wards which are subdivisions where voters elect representatives for various city and county offices. There are six wards in Cohoes. Especially in lower wards One, Two, and Three, the social and political lives of residents centered around their respective ethnic churches and schools, which often taught students both in English and in their native languages: French, Polish, Ukrainian, and Russian.

Big Mike had lived in the primarily Irish First Ward. Southeast of the First Ward, bordering the eastern branch of the Mohawk, was the Second Ward, home of Cohoes’s oldest business district on Remsen Street. The largest ethnic groups there were Poles...

Alle Preise verstehen sich inklusive der gesetzlichen MwSt.