Suchen und Finden

Introduction

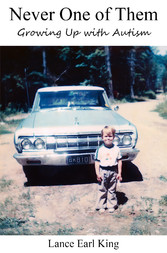

This book is a tale of inadequacy. It is also a story about how apparent shortcomings can sometimes be reimagined as great strengths. When I was a child, I desperately wanted to be six feet tall. After all, little boys are told to eat their veggies so they can grow up to be "big and strong." The social ideal of popular culture for males of our species is to be tall, dark and handsome. As it turned out, nature and nurture apparently had other plans for me. I grew up to be short, pasty, pudgy and somewhat average looking.

As I've discovered over the course of a lifetime, my physical profile is a less significant handicap than my neurology. That's because I have what is currently known as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). While autism awareness is on the rise, the general public is still unsure about what this diagnosis really means. Some people assume that being autistic means that I'm intellectually disabled, or potentially given to unexpected verbal outbursts. They might suppose that I'd be a poor choice for a dinner companion. Revealing that I have a neurological disability might conjure up images of me drooling on myself, having to wear a football helmet in public, or needing help using the bathroom. While some people on the autism spectrum are severely disabled, that certainly doesn't describe me. In fact, it takes a while for many people to catch on that I'm somehow different.

Large numbers of people have been erroneously led to believe that autism is strictly a childhood disorder that can be cured with dietary supplements, bleach enemas and other exotic treatments. Some people cling to long discredited research to argue that parents should resist immunizations for their children, fearing that these injections somehow trigger the onset of autism. A nearly exclusive association of autism with children in mainstream media reinforces the misconception that kids must magically outgrow autism by the time they reach adulthood. This steady drumbeat of misleading information concerning the nature of ASD perpetuates confusion among the general public.

Further complicating matters, people have been told by the leading autism advocacy organization that we have a terrible disease and thus constitute a tragic burden upon our families. They raise money in search of a cure without any meaningful consideration of what we have to offer the world. Oddly enough, this so-called advocacy organization claims to speak on our behalf, but bars autistic people from actually speaking at their events. While they have done some good work, their core philosophy is opposed to the self-advocacy practiced by many of us on the autism spectrum today. In view of this paternalistic approach to autism, it's no wonder that the general public would suppose that we lack the mental faculties to speak for ourselves. We are denied a voice in their organization, and instead the youngest among us are set forth as pitiful exhibits to raise money.

Autism is a neurological disorder, but not necessarily an intellectual handicap. In fact, many autistic people are highly intelligent and manage to get through our adult lives without ongoing support from others. Most adults of my generation and earlier had no choice but to adapt as best as we could without any sort of clinical intervention; the severely afflicted faced the prospect of being institutionalized at a time when ASD was commonly mistaken for mental retardation or schizophrenia. Some of us autistic adults thrive in specialized fields, but may fall a bit short when it comes to social graces or managing certain aspects of daily life.

I managed to survive the first 43 years of my life without a formal diagnosis. I'd moved out of my childhood home by my mid-20s, and in spite of some challenges, I've lived a more or less normal adult life. There are severely autistic people who do need lifelong care. Some have intellectual disabilities. Others are non-verbal. Autism is often accompanied by comorbidities such as ADHD, anxiety and depression that can make life more complicated. People like me are encumbered just enough by our neurology to appear outwardly normal most of the time, but we struggle socially in ways that aren't always obvious to the casual observer.

The autism spectrum is precisely that: a spectrum. What might be called classical autism usually presents a range of symptoms, among the earliest of which to manifest is delayed language development. In some cases, autistic children will start to develop speech normally, then regress and become non-verbal for an extended period of time before eventually speaking again. Others will remain non-verbal for life. In the mid-90s, a new diagnosis, Asperger's Syndrome, entered the diagnostic vocabulary. Aspies, as they frequently call themselves, exhibit milder overall symptoms and do not typically exhibit delays in verbal development.

As of 2013, Asperger's Syndrome was officially removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5). It has since been subsumed into the broader category of Autism Spectrum Disorder. As I was clinically diagnosed in 2014, my diagnosis came too late to be classified formally as Asperger's Syndrome. Based on the studies and literature that I've read, in addition to countless hours spent perusing online discussion forums and personal reflections over the course of a lifetime, I'm confident in saying that had I been diagnosed a year earlier, I would have been categorized as an Aspie. The term remains in use by experts outside of the US, including English psychologist, Tony Attwood. His book, The Complete Guide to Asperger's Syndrome, is widely cited as an authoritative resource on the subject.

When I was a child growing up in the 1970s, only the most severe cases of autism were recognized by the mental health profession. Milder forms of autism like mine escaped recognition by teachers and anyone else who might have intervened. There wasn't a clinical category at the time to describe kids like me. I was simply regarded as weird, quirky or socially awkward. Despite being immature for my age, I was placed in a regular classroom. Complicating matters, my birthday is in July, so my classmates were mostly older than me due to the age cutoff for school enrollment. As a result of these combined factors, I was doubly unprepared developmentally to deal with the social challenges of school.

When I was a little older, my mother told me that in first grade my teacher had commented on my report card that, "Lance is a good boy, but he doesn't play with the other children." As a diagnosed adult, I am now in a much better position to understand that my lifelong habit of selective, limited socialization was consistent with the neurological peculiarities common to all autistic people: we have difficulties with social interactions. The word autism essentially signifies “self-ism,” suggesting that autistic people mentally inhabit our own, individualistic worlds. While this characterization may not be entirely accurate, what preoccupies our thoughts is often not the same as what concerns neurologically typical people.

At some point in elementary school, my class was instructed to write what we'd want to have inscribed on our gravestones. I don't recall the specific lesson that led to this morbid writing exercise, but I quickly came up with a phrase that distilled my feelings about living among humanity: “I was never one of them.”

I lived with a persistent, nagging sense that I wasn't truly human. That raw epitaph encapsulated how I've felt for much of my life, even well into adulthood. I knew that I didn't think like my peers on so many levels. I'm not talking about a temporary feeling of loneliness, but a profound alienation that has persisted over the course of a lifetime. As an adult, I have a better handle on why I felt that way, but back then I didn't even have the language to fully articulate it. There was an insurmountable social barrier between me and most of my peers that I had no means to explain or understand. I had a few friends over the years – usually one at a time – but belonged to no tribe.

Even where our intellectual capacity may be equal to or greater than our non-autistic peers, our social skills lag significantly. It's not that we're willfully thickheaded; we simply fail to understand the unspoken rules of social engagement that other people pick up intuitively from a young age. This impaired social development is the part of our brains that's broken – at least from the perspective of non-autistic (“neurotypical”) people. It's not a matter of trying harder to act your age or even possessing a willingness to conform. Our innate social programming is simply different in those areas. Telling someone on the spectrum to try harder at social interactions is a bit like asking a pig to try harder to fly. That's not to say we're completely unable to adapt to the neurotypical world, but it doesn't come naturally or easily, and we never fully master it. Our learned social behavior is an intellectual approximation of what neurotypicals do intuitively, and it's exceptionally hard work.

As an adult, I've learned how to interact in common, scripted dialog, and I can pass as normal in many...

Alle Preise verstehen sich inklusive der gesetzlichen MwSt.