Suchen und Finden

Chapter 1 Films and Psychopathology

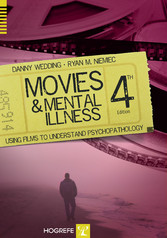

For better or worse, movies and television contribute significantly to shaping the public’s perception of the mentally ill and those who treat them.

Steven E. Hyler

For contemporary audiences, attending movies is an experience that provides catharsis and unites the audience with their culture in much the same way that the tragedies of Sophocles and Aeschylus performed these functions for 5th-century BC Greek audiences.

Glen Gabbard and Krin Gabbard

Introduction

In all of human perceptual experience, nothing conveys information or evokes emotion quite as clearly as our visual sense. Filmmakers capture the richness of this visual sense, combine it with auditory stimuli, and create the ultimate waking dream experience: the movie. The viewer enters a trance, a state of absorption, concentration, and attention, engrossed by the story and the plight of the characters. When someone is watching a movie, an immediate bond is set up between the viewer and the film, and all of the technical apparatus involved with the projection of the film becomes invisible as the images from the film pass into the viewer’s consciousness. The viewer experiences a sort of dissociative state in which ordinary existence is temporarily suspended, serving as a psychological clutch (Butler & Palesh, 2004) in which the individual escapes from the stressors, conflicts, and worries of the day. This trance state is further enhanced in movie theaters where the viewer is fully enveloped in sight and sound, and in some instances experiences the sense of touch through vibration effects. No other art form pervades the consciousness of the individual to the same extent and with such power as cinema. Many consider movies to be the most influential form of mass communication (Cape, 2003).

Hollywood took the original invention of the cinematic camera and invented a new art form in which the viewer becomes enveloped in the work of art. The camera carries the viewer into each scene, and the viewer perceives events from the inside as if surrounded by the characters in the film. The actors do not have to describe their feelings, as in a play, because the viewer directly experiences what they see and feel. To produce an emotional response to a film, the director carefully develops both plot and character through precise camera work. Editing creates a visual and acoustic gestalt, to which the viewer responds. The more effective the technique, the more involved the viewer. In effect, the director constructs the film’s (and the viewer’s) reality. The selection of locations, sets, actors, costumes, and lighting contributes to the film’s organization and shot-byshot mise-en-scene (the physical arrangement of the visual image).

The Pervasive Influence of Films

Film has become such an integral part of our culture that it seems to be the mirror in which we see ourselves reflected every day. Indeed, the social impact of film extends around the globe. The widespread popularity of online movies, DVDs by mail (e.g., through Netflix), nominally priced Redbox rentals at the street corner, the use of unlimited rentals for a monthly fee, and in-home, cable features like On-Demand make hundreds of thousands of movies available and accessible to virtually anyone in the world (and certainly anyone who has Internet access). No longer are individuals limited solely to the film selection and discretion of the corner video store. People now have wide access to films beyond Hollywood, including access to films from independent filmmakers, even those from developing countries. Moreover, with the affordability of digital video, neophyte and/or low-budget filmmakers can now tell their stories within the constraints of a much more reasonable budget without sacrificing quality (Taylor & Hsu, 2003); this increases the range of topics and themes that can be covered. Recent award-winning films such as Gravity (2013), Rust and Bone (2012), and Life of Pi (2012) were all shot using digital video.

We believe films have a greater influence than any other art form. This influence is felt across age, gender, nationality, and culture – and even across time. Films have become a pervasive and omnipresent part of our society, and yet people often have little conscious awareness of the profound influence the medium exerts. Films are especially important in influencing the public perception of mental illness because many people are relatively uninformed about the problems of people with mental disorders, and the media tend to be especially effective in shaping opinion in those situations in which strong opinions are not already held. Although some films present sympathetic portrayals of people with mental illness and those professionals who work in the field of mental health (e.g., The Three Faces of Eve, David and Lisa, Ordinary People, and A Beautiful Mind), many more do not. Individuals with mental illness are often portrayed as aggressive, dangerous, and unpredictable; psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, and other health professionals who 2. Film begets film: every new film draws on previous work with these patients are often portrayed as “arrogant and ineffectual,” “cold-hearted and authoritarian,” “passive and apathetic,” or “shrewd and manipulative” (Niemiec & Wedding, 2006; Wedding & Niemiec, 2003). Psychiatrists in particular have been negatively portrayed in the cinema (Gabbard & Gabbard, 1992). Films such as Psycho (1960) perpetuate the continuing confusion about the relationship between schizophrenia and dissociative identity disorder (formerly multiple personality disorder); Friday the 13th (1980) and Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) both perpetuate the misconception that people who leave psychiatric hospitals are violent and dangerous; movies such as The Exorcist (1973) suggest to the public that mental illness is the equivalent of possession by the devil; and movies such as One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) make the case that psychiatric hospitals are simply prisons in which there is little or no regard for patient rights or welfare. These films in part account for the continuing stigma of mental illness.

Stigma is one of the reasons that so few people with mental problems actually receive help (Corrigan, Roe, & Tsang, 2011). The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) estimates that only 20% of those with mental disorders actually reach out for help with their problems, despite the fact that many current treatments for these disorders are inexpensive and effective. In addition, there is still a strong tendency to see patients with mental disorders as the cause of their own disorders – for example, the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI) has polling data that indicate that about one in three US citizens still conceptualizes mental illness in terms of evil and punishment for misbehavior.

Psychiatrist Peter Byrne has pointed out that films rarely portray mental illness or mental health practitioners accurately, but he also makes the compelling point that the job of a director is to create a film that will generate revenue for producers and investors, and it is not necessarily their job to educate the public. In a recent article, he described five rules of movie psychiatry (Byrne, 2009):

1. Follow the money: film-making is a commercial enterprise and producers may include inaccurate representations in their films to ‘give the public what they want’;

2. films within the genre;

3. Skewed distribution hides more films than censor ship ever did;

4. There are no mental health films, just mental illness ones;

5. If it bleeds it leads: violence, injury and death often ensure prominence of a story in both news and film. (Byrne, 2009, pp. 287–288).

Byrne’s points are well-taken, although we would challenge Number 4 because we have written a book titled Positive Psychology at the Movies (Niemiec & Wedding, 2014) in which we document nearly 1,500 movies that display character strengths and other healthy aspects of human psychology, including positive mental health. This edition of Movies and Mental Illness also describes many films that offer positive depictions of mental health.

Cinematic Elements

A film director must consider countless technical elements in the making of a film, often orchestrating hundreds of people, many of whom monitor and pass down orders to hundreds or thousands of other collaborators. There are three general phases involved in making a film.

The time spent prior to filming in the preproduction phase is often seen as the most important. Many directors storyboard (draw out) every shot and choreograph every movement for each scene to be filmed. Countless meetings with each technical supervisor (e.g., cinematographer, costume designer, set designer, electrician) are held to facilitate preparation, coordination, and integration. The director will also scout out locations, work with casting appropriate actors and actresses for the various roles, and may rework the screenplay. In the production phase, the director attempts to film his or her vision, working closely with the actors and actresses to encourage, stimulate, guide, or alter their work, while carefully monitoring camera angles, lighting, sound, and other technical areas.

Alle Preise verstehen sich inklusive der gesetzlichen MwSt.